Diver with A5800 Rebrether and hand held sonar

Part Of The Team

By David Strike

Accounting for more shipping losses during the Second World War than any other weapon, mines - and the measures developed to neutralise them - have played a pivotal role in the evolution of military diving. It's a relationship symbolised in the crest of the Royal Australian Navy's Clearance Diving Branch; a diving helmet superimposed onto a tethered mine .

Unlike the contact mines of WWII, the influence mines of today are technologically sophisticated packages triggered by acoustics, changes in pressure, magnetic influences, or any combination of the three. Rather than detonating against the hull of a ship unlucky enough to run into them, an influence mine is positioned on the sea bed in up to 40 or more metres of water. Activated when a target vessel passes overhead the mine detonates, creating a huge gas bubble of vaporised water that, expanding as it ascends, forms a hole in the water beneath the ship. Unable to remain afloat, the ship falls into the hole, breaks its back and sinks .

Combating this threat is akin to playing a game of three dimensional chess in turbid waters, tidal flows, currents, silt and shifting seabeds; an evolving art form rather than a science and one in which the mine counter measures element attempts to second guess the minefield planner's intentions and the technology that he's using .

Despite an impressive array of mine counter measures resources - that includes purpose built vessels like the new 'Huon' Class Mine Hunters armed with sonar and ROV's - the shallow water approaches to ports and harbours, as well as the areas around wharves and buoys, still require the services of divers .

For Lieutenant Commander Peter Day, overseeing Mine Counter Measures is an important aspect of his job as Commanding Officer of Australian Clearance Diving Team One, one of the world's elite diving forces .

Diver with A5800 Rebrether and hand held sonar

Functioning as self-sufficient units capable of almost indefinite deployment into the field, the R. A. N.'s two Clearance Diving Teams (AUSCDT One, based at HMAS Waterhen in Sydney, and AUSCDT Four at HMAS Sterling in Perth), each consist of about sixty personnel organised around an identical Command structure .

With a Commanding Officer, Executive Officer, Warrant Officer and full support personnel, each Team supports three fighting elements - the UBDR (Underwater Battle Damage Repair); the MTO (Maritime Tactical Operations); and MCM (Mine Counter Measures) - two of whom (the MTO and the MCM) have Mine Counter Measures functions .

Structured along identical lines each element consists of one Officer, responsible for maintaining the operational readiness of his section and a Chief Petty Officer who, as well as being a diving specialist, attends to the day to day maintenance of those specific skills, (like weapons and small arms training, bush navigation and combat survival training), that give the teams their operational edge .

Not all mines are targeted against shipping. On occasion they're employed against the mine counter measures assets themselves; the mine sweepers and mine hunters that perform the Deep Water (DW) operations; as well as divers carrying out VSW (Very Shallow Water) and SW (Shallow Water) detection and disposal. Mines are also a potent weapon in halting or slowing down amphibious beach landings .

While those mines seeded below the high water mark are targeted against amphibious landing vessels, those placed above it are usually of the anti-personnel variety. Rendering these mines safe is a function of the amphibious reconnaissance divers of MTO. As a clandestine force going in under cover of darkness, the MTO operate in Very Shallow Water, placing charges on all of those mines that they discover in a field before retreating and firing them remotely .

The overt mine counter measures responsibility, (that of disposing of mines discovered in Shallow Water), belongs to the MCM element themselves .

(Although capable of operating effectively to much deeper depths, the operational training focuses on the shallower ranges, roughly between 9 and 45-metres, where reduced decompression obligations apply.) "Although a diver is unlikely to be the target of a minefield planner there' s always a degree of uncertainty when dealing with a live piece of ordnance." Says Lt Cdr Peter Day. "Our tactics are developed to determine how far off we can reasonably approach a known mine type to place a charge .

But that's a known mine. It's possible to have a completely different set of algorithms and instrumentation within a mine of the same shape. You can never be certain exactly what's inside it! "To keep our divers as safe as possible our tactics for dealing with mines are developed around the worst case scenario. For that reason we conduct a stringent series of checks on the diver and his equipment before he enters the water to ensure that they both have as low a magnetic and acoustic signature as possible," Because Mine Counter Measures diving requires relatively long duration underwater, coupled with a need for both acoustic and magnetic hygiene, the MCM divers use the A5800 semi-closed heliox rebreather (a derivative of the USN Mk 16), with a depth capability of 90+ metres. Even the diving knives are made of beryllium, a metal so toxic that it will poison anyone unfortunate enough cut themselves on the blade! "It's an evolving field and as a new mine type comes into the picture we develop tactics to dive against it." Peter Day continues. "We carry out considerable research to determine what a piece of ordnance is and what the procedure is to render it safe .

"To maintain the skills to do that requires continuous training. If the publications we use on mine identification or Render Safe Procedures are not complete, or if the information just isn't available, we still have to deal with the job. In those instances we rely on the judgement of the person tasked with rendering the mine safe. He doesn't rely on guesswork! They're all carefully considered actions based on knowledge and experience of dealing with a particular mine type and which are then incorporated into the data base on dealing with that specific threat .

"We also work closely with the DSTO ( Defence Science and Technology Organisation) in developing procedures against certain types of mines. They provide a lot of the intellectual input that help us develop appropriate tactics." While mine technology has taken a quantum leap, searching for them remains a painstaking and patient process. Parallel jack-stays are laid along the sea floor allowing progressive scrutiny of the area to be searched. Working in pairs divers can employ a snag-line strung between them or, because it's possible to initiate the firing train in a sensitive mine, they may use hand held sonar units to seek out a target .

Containing sophisticated electronic packages, a direct approach on to a mine is fraught with risk. (The mine may, for example, have an acoustic trigger to 'wake' it up and a magnetic trigger to initiate the firing mechanism. A whale swimming past won't cause it to explode but a targeted ship, with metal in it, will!). For this reason the searching diver, having detected a mine, places a marker in the vicinity to help guide the supervisor to its position .

Unless the mine is the first find of its type, and therefore one that needs to be brought to the surface for 'exploitation', then the preferred method of disposal is to detonate it in situ by placing a charge right beside it .

More often than not, however, the mine's close proximity to sensitive areas makes it necessary to render it safe before bringing it to the surface for examination and disposal .

The Render Mines Safe (RMS) procedure is carried out by the Supervisor who places and remotely detonates an explosive charge in the vicinity of the mine (rather than on the mine itself, a process which may trigger a sympathetic detonation!). The aim is to collapse the instrumentation and disrupt the firing mechanism through over pressurisation .

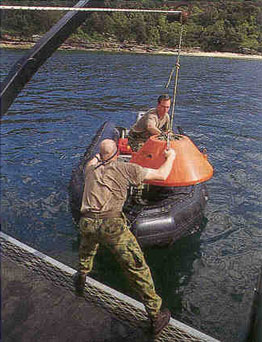

Recovering Manta exercise mine

The supervisor will then carry out a verification dive to look for cracks in the mine's casing, air bubbles, or other signs that the charge has rendered the mine safe for handling. Ideally the RMS procedure cracks the casing and floods the electronic componentry .

The person supervising each job is the person who determines when the mine is safe to move. (On one mine tackled by AUSCDT Three during the Gulf War - an Italian, 'Manta' with a fibre glass body making crack detection difficult to see - the procedure had to be carried out three times before the supervisor felt confident enough to continue with the surface lift.) Once the supervisor is satisfied that the RS procedures have been effective a lifting bag, made of non-magnetic material, is attached and - when the team has withdrawn to a safe distance - remotely activated. Once on the surface a tow line attached to the lifting bag is used to move the mine to a pre-determined beach where, in about 2-metres of water, a transition buoy and tow rope have previously been positioned .

Tripod in place over a mine previously rendered safe

Connecting tow line and tow rope together with karabiners the rest of the team retreats, leaving the supervisor - who is positioned outside of the mine's blast and fragmentation range - to remotely pull the mine up onto the beach and into position under a tripod where he can work on removing the mine's fuses .

"Ideally we like to have the tripod pre-set so that the supervisor spends as little time as is necessary working over the mine." Explains Chief Petty Officer Steve Woodman, one of four Clearance Divers to be awarded the Conspicuous Service Medal for EOD work in Kuwait during and after the Gulf War .

There is always the risk that the render safe charge has only made the mine' s sensors temporarily 'dizzy' rather than disabling them. A situation in which the mine, alerted by movement will wake up, 'look' at what is approaching and, if it perceives a threat, initiate detonation .

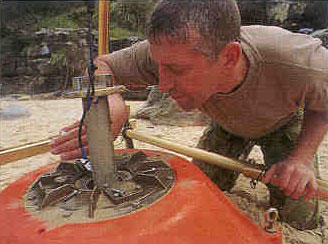

Supervisor checking the fuse wiring in a Manta mine

Both above and below the water, the diving Supervisor usually adopts a 'one-in-three' approach to a mine, taking one step then stopping and counting to three. Activated by the movement the mine will 'wake' up, 'look ' and, failing to detect further activity, turn itself off and go back to sleep. This procedure is repeated until the supervisor is close enough to visually examine the mine and determine the appropriate course of action "You have to remember", says Steve Woodman, "that its been on the bottom of the sea; it's had a big explosive charge initiated close to it; it's been lifted from the seabed to the surface; it's been towed, bobbing around, through the water; and it's been dragged up onto the beach. If it hasn't initiated in all that time then there's probably a good chance that it's not going to. However!!!! "The operator may drop the 'One-in-Three' approach", he continues, "and walk straight in without taking that precaution. He may, for example, say, 'This is definitely not a magnetic mine', and he'll dispense with magnetic hygiene, wear his watch and use a normal screwdriver as opposed to using one made of beryllium, or other non-ferrous material. It's his call .

"Usually, however, there's nothing metallic on the operator and even the nuts, screws or bolts removed in order to extract the fuse are left on the casing so that there is no change or disruption to the magnetic field." Having removed all of the retaining devices, a bridle is attached to the fuse and hooked on to the tow line. Again retreating to an area outside the blast and fragmentation range, the supervisor will remotely lift out the fuse to a position where, on his return, he is able to look into the well and check the wiring. Once he's convinced that the mine has the wires, cables and sensors that it's supposed to have then he can be fairly confident that it hasn't been tampered with .

Research will tell him what procedures to follow. "There might, for example, be eight wires", says Steve Woodman, "and the operator has to first cut the blue wire followed by the white wire. The decision on what to do is his alone. He may cut it, or he may decide to try and do it remotely by using one or other of the tools in our render safe arsenal. We can fire bolts to sever fuses or use water jets to disrupt a package or thin-skinned munition." While locating mines and placing charges, particularly in murky waters or strong currents, is dangerous work, mine counter measures forms only part of the Clearance Diver's role in EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal). He's also called upon to deal with surface threats, from bombs, Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) and booby traps through to ordnance from WWII .

Because there will always be, in the foreseeable future, a role for a guy to go down and dive on a mine, AUSCDT One (and AUSCDT Four) are constantly honing all of their many skill levels. Working closely with the Americans (the Teams have two exchange positions with their American counterparts) and other countries around the region, the Team divers maintain their readiness through continuous operational training with other Forces .

"It's a situation that benefits all parties", says Lt. Cdr. Peter Day, "and one that ensures an equal transfer of information. It's certainly not one-way traffic! Our Clearance Divers' are very capable people with exceptional abilities who provide the RAN with a range of skills not found in other Navies." And with just two operational Teams, the Clearance Divers of AUSCDT One and AUSCDT Four are among Australia's scarcest assets .

--ENDS--- GROUP PHOTO .

Back row; Glen Mitchell Middle Row: Pincher Martin; Steve Woodman; Geoff Symes; Ben Abbott; Michael Voytas; Buster Stancil; Craig Moore; Front Row: Paul Wheeldon; Richard James;

>Breakout Panel # 1 Training The RAN conducts three levels of training for Clearance Diving Mine Counter Measures operations. Basic training for a Navy Clearance Diver is in the order of six months. Approximately one quarter of that time is spent in MCM training, with a similar period devoted to ordnance disposal functions for mines. During that time the diver learns to use the specialised diving equipment employed by the MCM element; the search techniques used to find and safely identify underwater ordnance; and how to prepare charges .

Once a diver attains a certain rank and seniority they become eligible for advanced training. This teaches them to supervise both the diving and the MCM operation; the best type of search to employ in the prevailing environmental conditions; the procedures for rendering the mine safe, (a manoeuvre that usually takes place underwater), recovery of the mine to the surface and the extraction of its instrumentation package .

The route for Clearance Diving Officers is even more demanding. Having first gained their Bridge Watch Keeping ticket, completed the full Clearance Diving course and carried out the same advanced MCM level training as the senior sailors, the officers also receive further schooling in Mine Warfare .

Dealing with mine sweeping, mine hunting, command and control of Mine Counter Measures and Mine Warfare operations, mine laying, and the use and purpose of specific equipment carried on board the various ships, the Mine Warfare course trains the officer to recognise mine shapes, their characteristics (whether, for example, they're 'woken up' by an acoustic signature and fired on a magnetic impulse), and - with a reasonable degree of certainty - what threat that particular piece of ordnance poses for the operator who must deal with it .

Armed with this comprehensive view of Mine Warfare and Mine Counter Measures, the Mine Warfare and Clearance Diving Officer is able to pit known mine types against particular Mine Counter Measures platforms (a diver or a ship) and - because it's impossible to be certain about what is inside a mine - in developing tactics for dealing with them .

-----------------------------

>Breakout Panel # 2 AUSCDT Three in the Gulf In January, 1991, AUSCDT Three was reformed with personnel from across the force and was despatched to Bahrain to help the U.S. Marines prepare for the proposed amphibious invasion of Iraqi occupied Kuwait. As Operation Desert Storm progressed the requirement for an amphibious assault lessened, the Team's primary mission became the Explosive Ordnance Disposal [EOD] clearance of the ports of Kuwait .

The twenty-three man team entered Kuwait by land on the 5th March. Joining almost fifty other divers from the US and Royal Navies they began the dangerous task of clearing wharves and warehouses of unexploded ordnance and booby traps before entering the oil blackened waters of the harbour to search for, and dispose, of sea mines .

During the next seven days AUSCDT Three cleared over 450,000 square meters of seabed, searching for both buoyant contact and influence ground mines .

An effort that represented seventy per cent of the harbour area cleared by coalition forces by the time the port re-opened to shipping. Their efforts weren't restricted to below the surface operations. During this time the Team also rendered safe three Iraqi seamines, carried out booby trap clearance on a nearby oil refinery and assisted US personnel to recover six anti-ship missiles from the Kuwaiti Girls Science High School .

Moving south, AUSCDT Three were next tasked with clearing the Kuwaiti Naval Base of Ras Al Qualai Ah. The ten day operation involved removing booby traps and rendering safe thirty-one sea mines. Back in Kuwait City the Team continued work on clearing the harbours and beaches that were Kuwait's lifeline with the world .

On the 11th May, after three and a half months deployed, AUSCDT Three returned to Australia to be disbanded and members returned to their parent Teams. During their time in the field they had cleared four ports, dealt with 60 seamines, cleared 234,986 pieces of ordnance and searched an astonishing 2,157,200 square metres of sea bed! They lost count of the number of booby traps that they had to contend with! AUSCDT Three had distinguished itself well in Kuwait and earned for the RAN Clearance Diving Branch an international reputation for skill and professionalism. Recognition of their achievements included the award of two Conspicuous Service Cross's, 1 Order Of Australia Medal, 4 Conspicuous Service Medals, an Australian Meritorious Unit Citation and an Admiral's Commendation .